Photo: Margaret Carmel/BoiseDev

The sixth time was the charm for Fabiola Jimenez.

After a frustrating search for a new two-bedroom apartment to share with a roommate, she finally found an affordable Central Bench rental after her sixth application. The privately managed, no-frills complex is one of the few left in the neighborhood offering rent below $1,000 a month, giving her enough cushion to keep up with her food costs, rent, and other expenses.

[Some Idahoans are struggling to access millions in rental assistance]

She’s bringing in nearly $15 an hour, working 30 to 40 hours a week at Fred Meyer, double Idaho’s minimum wage, so things are doable for right now. But, Jimenez, 23, worries about what could happen if her rent gets hiked up or if she gets slapped with an unexpected expense.

“You have to sacrifice things to get by,” she said, sitting on a bench outside her apartment. “It’s basically like, ‘well, I have enough money for a roof over my head, but will I have enough money to actually eat? Or what about a car repair?’ And especially with health insurance being so expensive, I wonder “what if something happens to me and I can’t afford it?”

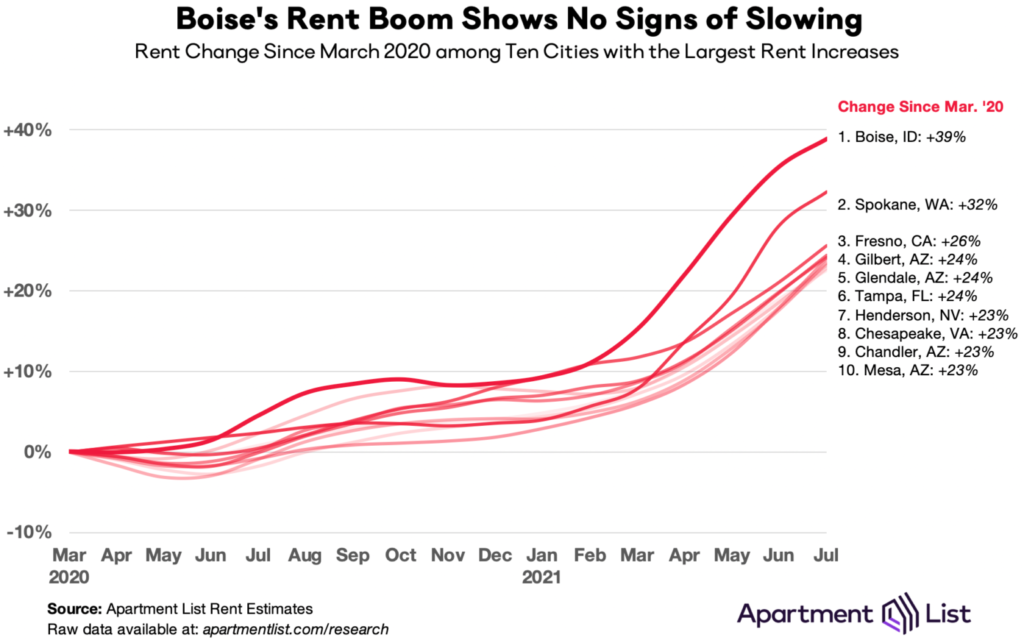

This is not an unfamiliar story in the Treasure Valley for hourly wage workers. In Boise, service workers, daycare staff, warehouse employees, and others making less than $20 an hour struggle to keep their heads above water. Wages have risen in recent months as the economy roared out of the pandemic, but they still haven’t kept pace with the fastest-growing rents in the nation.

This leaves minimum wage workers like Jimenez with tough choices. Should they move further outside of city limits and start pouring more of their money into gas and car maintenance? Cut down even further on household expenses? Double up in an apartment with another family? Or leave Idaho altogether for a cheaper place and say goodbye to their support system?

‘So what options are we going to have next?’

Jimenez wanted to plan ahead.

When she was still living with her parents on the Bench, she started working at Fred Meyer in early 2019. The job helped her pay bills and put money aside for herself to find a new place. She wanted to make sure she had a solid emergency fund saved up before she struck out on her own, but Jimenez never anticipated the double-digit rent increases and below 1% vacancy rates she would encounter.

She’s bounced back and forth between living with her parents and elsewhere in the past few years, but she said her relationship with her parents changed, and she no longer can move back in. Jimenez never went to college because of the debt she would incur to get a degree, leaving her at her Fred Meyer job to pay the bills. She’s toyed with finding another position, but the idea of moving to an unfamiliar job and the possibility of a layoff after the upheaval of COVID-19 worries her.

[A love letter to the Boise Bench: Why I love this always-changing part of Idaho]

One possibility she’s considered is moving to the outskirts of the Boise metro area, but rents are rising there too. She’s stuck.

“I’ve looked at listings in Kuna, Nampa, and Caldwell, and they have gone up significantly, so I go ‘oh, so what options are we going to have next?’” she said. “I’ve known people who have driven an hour to work and back because the housing they have is cheaper, and they can’t transfer to another location. Gas can easily accumulate. That’s the one thing people easily forget.”

A dream deferred

Housing is getting tougher and tougher to find throughout the United States than at any time in recent history. A new report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition found it requires the average American to earn $24.90 per hour to comfortably afford a two-bedroom apartment or $20.40 an hour for a one-bedroom rental. Nowhere in the country can a minimum wage cover rent.

Idaho ranks 35th in the nation for the wage required to afford rent, but the study found that the average Gem State resident would still need to earn $17.36 per hour to rent a two-bedroom. It would take 96 hours of work time a week to afford a two-bedroom apartment, which is difficult for single parents or caregivers for other family members.

These numbers mean Jimenez’s dream of settling down with her own home is getting farther and farther away.

“Personally, I wanted to go to college, get a career and get my own little house and just live out the rest of my days,” she said. “…I just don’t want to struggle anymore instead of having to stress day by day, paycheck to paycheck about ‘how am I going to pay for this’ or wondering ‘am I going to be homeless.’”

The night shift shuffle

Things aren’t easy-going for many households with two income earners either.

Callista Moore, 34, and her husband are trying to make it work, but with every step forward, they get knocked two steps back. Between the $1,040 monthly rent plus utilities, child support for her husband’s son, who lives out of state, and the costs of raising two children under 10, things haven’t been easy.

Until recently, Moore worked as a cook at a daycare, so she was eligible for a discount on her four-year-old daughter’s preschool costs while her seven-year-old son was in school. But, she had to leave the job when her daughter was dismissed from her preschool class. This meant Moore no longer had the childcare costs taken out of her paycheck, but she was left without a place for her daughter or her job because she needed the childcare.

Now, she took a new position at Scentsy on the manufacturing line making $15 an hour on the night shift. This means she watches her daughter during the day while her husband is at work as an apprentice electrician, and he takes over watching the kids when he comes home, and she heads off to the manufacturing line.

[Level up: Idaho programs help skill up workers for new jobs]

They’re making it, but they aren’t getting much sleep. And her husband doesn’t have much time to study for his upcoming journeyman’s test to become a full-fledged electrician. Taking the test doesn’t come cheap, so they are hoping he can pass on the first try to start making more than $18 an hour. Most months, they still have to stock up on groceries at a food bank to get to the end of the month and make sure rent is paid.

“It seems like every time he gets a little bit of a raise, something comes up we have to pay for,” Moore said. “Before we had childcare, and now he still pays child support, and we had to get a new vehicle at some point, or maybe rent goes up. That extra little bit of money from the raise just goes to the rent or utilities or something.”

Moore moved to Boise when she was ten years old and moved away for a time in her 20s, but she always hoped to come back to Idaho and raise her children here. Now, she and her husband are contemplating leaving for a cheaper area, which would mean leaving behind their community.

“I wanted my kids to be raised here, and now all of this is going on, and it’s making it harder,” she said. “My Mom is here, and if we were to leave, she’s by herself. It’s like, what do you do? Do you stay and try to figure out how to deal with it or do what’s right for your family and leave to allow us to live more comfortably?”

Falling behind makes it difficult to catch up

Jesse Tree Executive Director Ali Rabe hears stories like this all the time.

As the housing crisis has continued to heat up, Jesse Tree pays thousands of dollars a month in rental assistance to help low-income Boiseans catch up from missing rent payments to avoid eviction. In July alone, the nonprofit provided case management and rental assistance to 115 households.

Rabe said nearly everybody they serve is working, has a serious disability, or they are a senior citizen struggling with Treasure Valley rents on a fixed income. Before each family can get assistance, they have to work with a case manager to talk through their options, go through a budget to cut out unnecessary expenses, and make sure they are in a sustainable situation once they get a financial boost.

Oftentimes her staff advises their clients to take on a second or a third job, like driving for Uber or delivering for DoorDash to add extra income. But often, it’s not the lack of work that’s the problem. It’s the brutal, hundreds of dollar rent increases.

“People think folks experiencing homelessness are lazy, and they don’t want to work, but the fact of the matter is that most people that are being evicted or becoming homeless simply can’t afford to pay their rent,” Rabe said. “Once you fall into homelessness or experience eviction for the first time, you are much more likely to experience it again because having an eviction on your record causes barriers to finding housing and job opportunities.”

Reaching for small goals

It gets even more challenging to make ends meet in Boise if you can’t work full time.

Cricket Silo, 22, is disabled and has chronic illnesses that come and go. Some weeks they are fine to work, but others they can’t manage. Silo makes a living with a conglomeration of art commissions, odd jobs like dog-walking, and other freelance projects. They live with three other friends in a house, splitting the roughly $1,600 a month rent.

The inconsistency of the situation makes it hard to cobble together rent by the end of the month, let alone tackle their growing medical bills that have gone to collections. To get by, Silo tries to save up money from good weeks where they get a lot of commissions and dog walking gigs to save for the bad ones, but it’s a tough balancing act. Most of their food comes from food banks, dumpsters, or friends after they got turned down for a food stamp card due to problems obtaining documentation from a previous employer, Silo said.

“The future is kind of unclear,” they said, sitting in a Boise Bench park last month. “It’s the extra challenges of having an unpredictable illness that I might feel better one week and the next week I can’t work. What I’m looking for in the future are things like ‘I’m going to get my car fixed’ or other small goals like that.”

Silo has a strong bond with their roommates, and they hope to continue to keep living together. But the housing market threw the housemates for a loop recently when the owner of their home informed the group that they plan to move back to Boise next year and live in the home themselves instead of renting. This gives Silo a definite end date when they will need to find a new house for their group, but the tightening housing market makes their future even more uncertain.

Watching the rents rise, student debt pile up, and healthcare costs increase for their friends, Silo is getting frustrated with the limited choices they and other members of their community have.

“I think a lot of the things I dream and hope about I think could be attainable without economic means,” they said. “But when I think about the economic situation, I dream about seeing my friends not having to worry about the same (situation) and not being kept in debtors’ prisons essentially.”

source:

By Margaret Carmel – BoiseDev senior reporter

Under $15: Low wage workers in Boise face tough choices in tight housing market